Crooklets to Sandymouth

It is arguable that this is one of the most spectacular coastal walks that you will find anywhere. Unspoilt dramatic scenery, ever changing and to Bude people, this is what makes our coast so special and valued. Local people, throughout recent times, have refused to allow building on our Downs and shoreline and today we all reap the reward.

Photo of Higher Sharpnose, just to north of Sandy Mouth, courtesy of Thematic-trails.org

We are starting at the Bude Surf Life Saving Club, as this is where Surf Life Saving began in Britain in 1953. An Australian, Alan Kennedy is considered the founding father of the Service in Britain. Following high positions in Surf Life Saving in Queensland, Australia. His work took him to England and to Bude in May 1952. He fell in love with the town and the surfing here, but he realised the inadequacies of life saving skills and equipment. So, he wrote to Surf Life Saving Australia (SLSA) asking for some basic equipment, which was duly received by August 1953. There followed a period of intensive training and soon there was a squad of twelve members who had achieved, what was then the Australian Bronze medal. The club grew fast over the coming years and has now logged over 1000 rescues and pathed the way for Surf Life Saving in Britain.

Take the steps to the left of the Club House and join the path to the left, leading to the cliffs, but stop before the gate.

At the cliff-gate look down onto Crooklets Beach below.

It is hard to imagine that 6000 years ago Crooklets Beach was a forest of Oak and Hazel. And, the shoreline was around 600 m further westward as were the cliffs themselves. The remnants of the forest, now fossilised, reveals itself after heavy winter storms. A little over one hundred years ago bones were found amongst the fossil wood; could these have been the bones of our earliest hunter-gather visitors? Or were these bones those of an unfortunate sailor, whose ship met the fate of many, on our shores?

The fossilised forest as recently exposed

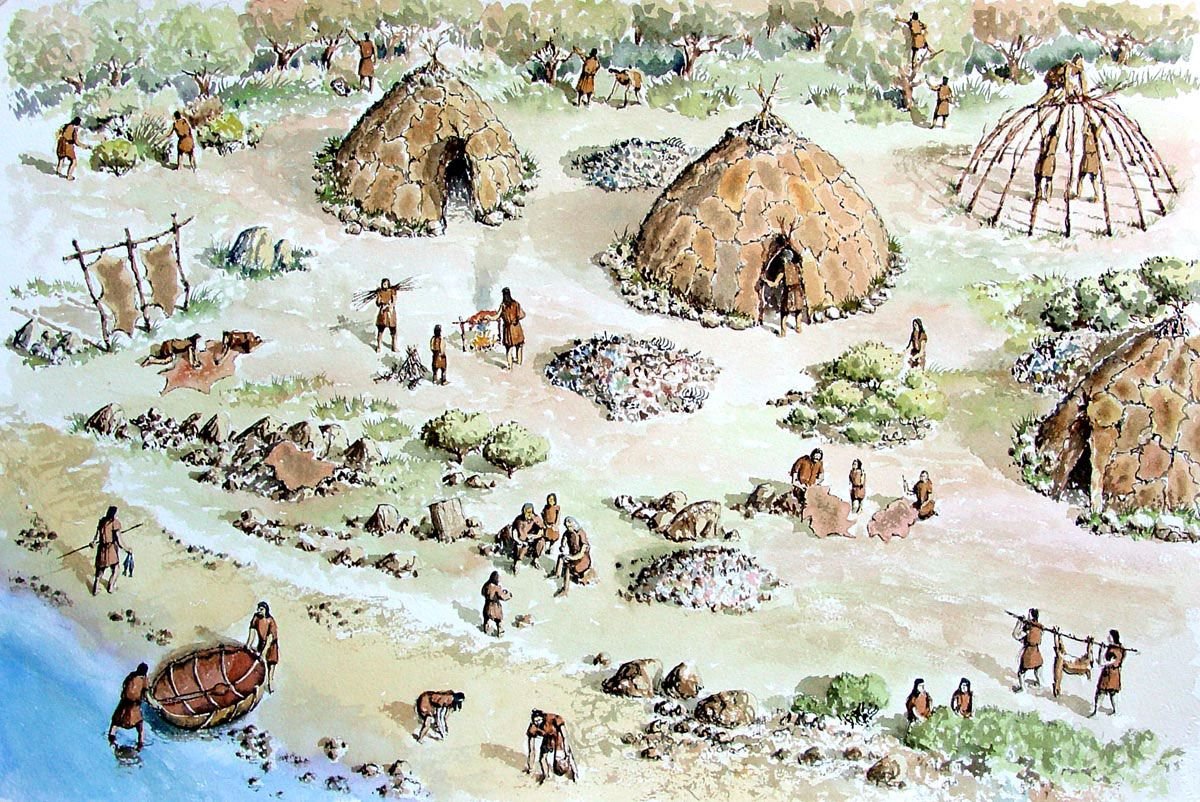

Walk up through the gate and take up a position overlooking the scene to the south. You can see our breakwater at the mouth of the harbour- known in the distant past as Bede’s Haven. In fact, in the very distant past, this really was a safe refuge extending three and half kilometres into the countryside and in places, a kilometre wide; a safe landing that attracted a band of Mesolithic hunter-gathers, who we know summer camped here and fashioned flint tools from stones deposited on the beaches by glaciers. The fragments of flint from their workings now provide archaeologist with the evidence of their passing. They used the natural north and south tidal flows along our coastline to aid their progress in coracle boats.

As you start to climb the rise ahead look to your right over into the field away from the sea. You should be able to see a large mound. The is the first of many Bronze Age bowl-barrows, or burial mounds.

Life had moved from hunter-gathering and transitioned to the Neolithic people and tentative farming and on to the Bronze Age. A much more organised culture who spent at least the summer on our local Moorland, probably returning to winter pastures locally. Incidentally, the Cornish word for a Barrow, or mound, is Crük and it seems a small step to accept that the name Crook-lets, refers to the three small barrows that were on this hill.

As you walk along and glance down onto the beach, the skeletal remains of an eroded cliff line will be always present. If you see a structure with a “V-shape” pointing towards the sea, this was an anticline structure; a structure pointing towards you is a syncline.

Follow along your route northward to a location we call Earthquake. It will obvious how has this name as the whole cliff face is slipping its way to the sea. Huge cavities opening up in the process. This section of cliff will head seaward soon.

In 1893, some men were quarrying here just below where you are standing when the top surface began to fall in. Small stones rained down on them and eventually a burial grave, or cist, with a capping stone of a rock unusual type for this location, plus a container of cremated bones. These were promptly reinterred at the Poughill churchyard where the grave can be seen today, topped with, what we now know to be, a very large granite capping stone.

You can now head down towards the gate to the right of the Bungalow ahead.

As you walk towards the gate, half-way down, again look to your right and just discernible is yet another Bronze Age burial mound. This was a large barrow but now blending with the Downs.

(And, incidentally, the whole of these Downs were once the 12 hole “Bude Cliff Golf Club” – used mainly by guests of the Falcon Hotel. Bude at this time also had a nine-hole ladies’ course, near to Crooklets beach, and an eighteen-hole men’s course. Golf was introduced to Bude in 1891.)

Having passed through the gate by the bungalow, walk just a few more metres to a narrow path leading down to Northcott Mouth.

(Just forty years ago you would have been able to walk in front of this bungalow, but the sea is fast eroding this cliff line here.)

Ahead of you is a scene that has not changed much over the last two centuries

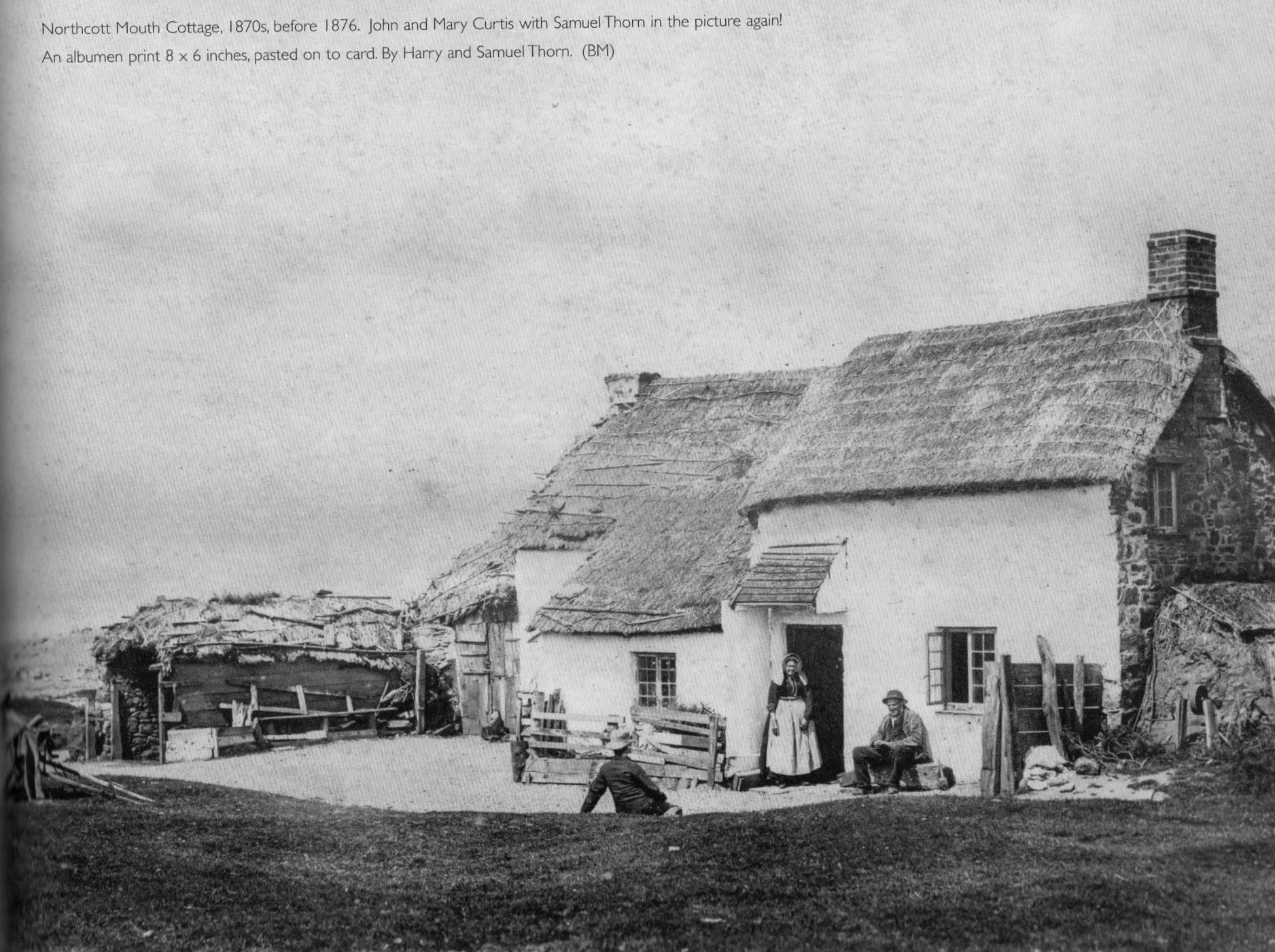

This photograph shows the cottages in the 1870’s; the occupants probably eking out an existence in a very isolated spot

Same bungalow in the 1870’s, showing in the picture John and Mary Curtis. John worked at the local farms and his wife would have harvested the bounty of the sea and shoreline – not to mention catching rabbits on the downs. They would have harvested Laver Seaweed to sell for export to South Wales where it was much in demand. And of course, there were winkles, mussels, shore crabs and other seaweeds for their own table and flotsam and jetsam from ships and shipwrecks, which provided them with firewood. Also in the picture and sitting on the grass is the photographer Samuel Thorn.

(From the photograph it seems that this wood was also used to weigh down the shed roof and, the thatch of the house is also tied down against the ravages of the westerly winds. To the right of the house, a hand driven grinding wheel also sit ready to sharpen all the instruments required for the work and home needs. The rock outcrop just on the beach are named on O.S. Maps after this family, “Curtis Rock”.)

We have here a remnant of the wartime, when these dragons’ teeth protected our shores from tank and other craft landings.

(Hopefully you now have the energy, and the head for heights, to climb the zig-zag path to the top of the cliff, which has the endearing name of Bucket Hill. If you do not fancy the climb there is an option path on the landward side of the hill – less effort, a little longer, but no less picturesque but it does give you an excuse to take a coffee at the little caravan halt.)

As you approach Menachurch Point, there standing defiant is another Bronze Age Barrow. If you look carefully at the outline of this barrow, you can actually see the outer circle formed as the builders trenched up the soil to form the mound. The prefix “mena”, incidentally, derives from the Cornish word “meneth” meaning hill.

(The term Bronze Age is being used here, but in truth we do not know; they are believed to have been a feature of the Late Neolithic to Late Bronze Age cultures, that’s between 2500 to 1500BC. Like so much of our extraordinary archaeology in this region, there has been shamefully little use of modern dating procedures to give a sound chronology to our history.)

Your walk now takes you along the uninspiring named locations of “Pits”, that is Westpark Pits followed by Sarshall’s Pit. The Sarshall name is a mystery. The Pits may just reflect the winter water-logged hollows, but they are shown on O.S. Maps as “disused”. So, there may have been some workings here in the distant past.

As you descend down towards Sarshall’s Pit you pass one of the target Butts used for live round rifle and machinegun training during WW11 by the Home Guard. The Butts were built by a group of local builders who were formed into a single organisation for the duration of the war. They comprised men who were either too old to fight or deemed unfit due to health reasons. Many of the men did, however, join the Home Guard.

Fifty metres further on, glance down to the beach below, and you may see the skeletal remains of the Belem steamship boilers. The ship was wrecked on the 20th November 1917. It was enroute from Algiers to South Wales. A German built ship, in Portuguese ownership at time of the wrecking, formerly known as the SS Rhodos, before being seized at the outbreak of the 1st World War.

Ahead of you your eyes will have more than once picked out the sight of the elaborate white domes and parabolic discs that is Cleave Camp GCHQ listening station, no doubt monitoring all that is going on in the high-tech world of digital ill doings, that seems incongruous against a backdrop of so much tranquillity and beauty.

In fact, Cleave Camp was built in 1938/9 as a training ground for Territorial Army Units using Anti-Aircraft, Bofars and Lewis guns. Various aircraft were used to tow a target which trailed out from the aircraft. This photo shows a Westland Walles fitted with a retracting mechanism used to release and recall the target- assuming it was till in one piece. Queen Bee remote controlled aircraft were also used. They were steam-catapulted into the air, with targets in tow. It was quite a spectacle at night to watch the tracer bullets and searchlights combing the night sky.

It was a bit “make-do”, for example, when the Bofars guns were firing, the gunner could not hear the command to ceasefire, so a piece of string was attached to his foot, which could then be tugged away from its position on the firing pedal!

The story of the Pilots is wonderfully told first hand by Pilot Officer, Bill Young in his book, “Cleave”, available locally.

(A little anecdotal story relates to the group of builders assigned to construct the air raid shelters at Cleave Camp early in the war. They may have thought themselves safe from action on this remote headland. But as they were digging out one of the air raid shelter pits, they spotted a German Bomber circling with one bomb clearly still to be used. They managed to pull each other out of the deep hole and run for cover as the bomb dropped. They then realised one of their number had been left down the pit. However, as they made their way back to their work, they found the missing man walking away from another building. He had somehow jumped out of the three-metre hole unaided. He could not say how he had managed it!)

As you near then end of your walk take a look at the terrain around you and you will see other pits, or cracks in the cliff tops. This is the start of the next cliff landslip. Water pours down these cracks, undermining the soil structure to the point that the cliff no longer has firm contact with the substrate, and the mass slips to the shoreline.

You have now earned the view down into Sandy Mouth with Lundy Island looming in the distance at the mouth of the Bristol Channel.

Sandymouth Café and a refreshing lunch or coffee awaits in the café below.

After coffee and lunch. You may be able to walk back to Bude along the beach. In fact, you should try to time your return walk with low tide during the lunch period. It is then possible to walk back to Bude along the whole length of the tideline. This can only be described as spectacular. Ask any local person and they will tell you that this beach return to Bude is what makes Bude so special to us all.

If you do choose to pop down to the beach or are heading that way to make a beach return, then you will be greeted by two little waterfalls that cascades down from the clifftop to the beach below. (One on the left, the other on the right.) This is a classic example of dozens of similar waterfalls along this strip of coastline where the small streams battle to erode a course to the beach but prevented from doing so by the erosion rate of the sea.

If you enjoy reading about our history without any adverts appearing, please help me to meet all the cost with a small donation.

For extra security, the link below will take you directly to a payment centre without an intermediate stage.

For more details of how this donation will benefit you and young local people to our area, please select “info” on the menu button.

Your payment will be much appreciated, however small, thank you.