Arundell of Trerice and Bude

Introduction

As with the Blanchminster family of Binhamy, Stratton, the Arundell family married into the wider aristocracy, including the Grenville family of Stowe, the Acland family (later of Bude) and the Carew family of south-east Cornwall.

As with the Blanchminster family, theirs is a background of famous Admirals, MP’s and Sheriffs of Cornwall. And, to this, one must include personal service to various Kings and Queens of their times, with ancestry going back to the Normans. The early family seat appears to have been at Arundel, in the west of the County of Sussex and they appear in Cornish records from around 1340. Some researchers conclude that direct ancestral line stems from a Nicholas Arundell of Little Hempston, Totnes in Devon. This is supported by the frequent occurrence of the names Nicholas and John, which has made this a researcher’s nightmare.

The Arundells were an important family and had great influence in so many places within England. The complexity and reach of the family necessitates that this account concentrates only on the family whose manor was at Trerice, just to the south-east of Newquay in Cornwall; it is they who will live from time to time at Ebbingford Manor (or Efford) and have a significant role in the story of Bede’s Haven (Bude)

Despite having a grand mansion at Trerice and other estates in Cornwall, many Arundell family members chose to live at Ebbingford Manor, for at least some of their time. It was situated on the south banks of the Neet estuary, where it could be reached, from the north shore of the estuary, when the tide was ebbing, and where it was protected from the strong ocean westerlies by sand hills to seaward. There was also a track on the south banks of the estuary from Helebridge- which at that time was probably still called La Ponte. The manor also had at least one, but possibly two, lime kilns as part of the premises. For some, it was probably a summer retreat.

This story will briefly explore the family background, leading to their move to Bede’s Haven (Bude). It will also show how a Sir John and Lady Gertrude Arundell, who came to the manor around 1553, changed the geography of the estuary forever, by building a tidal mill across the mouth of the estuary in 1577, setting in train a process that would develop this small community into a busy harbour, eventually leading to the town of Bude we know today. It will also explore the nature of Sir John and why he may have preferred the peace and solitude of Ebbingford to that of the political life in which his ancestors had been such important participants..

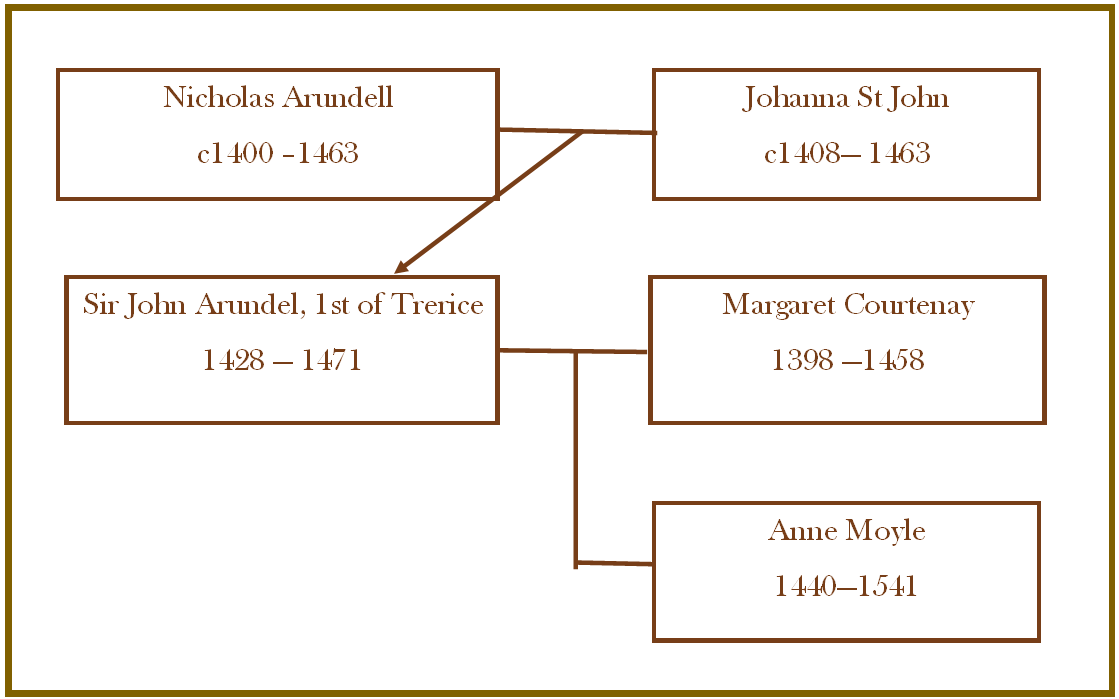

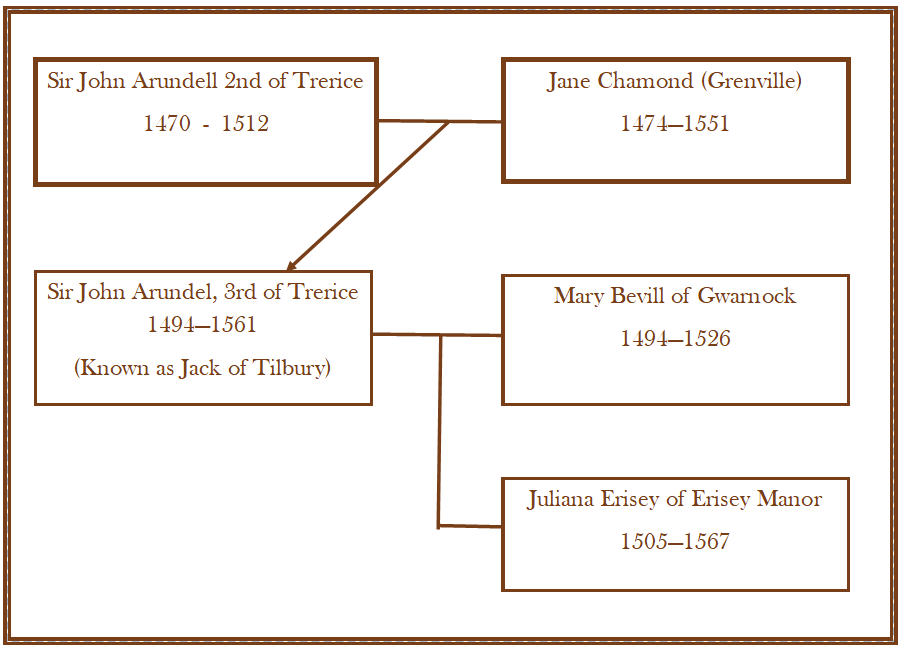

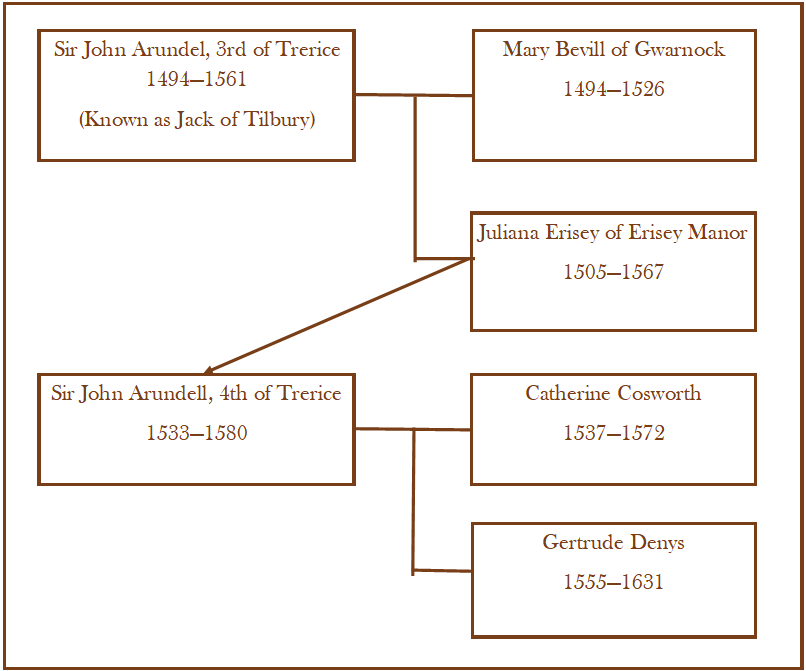

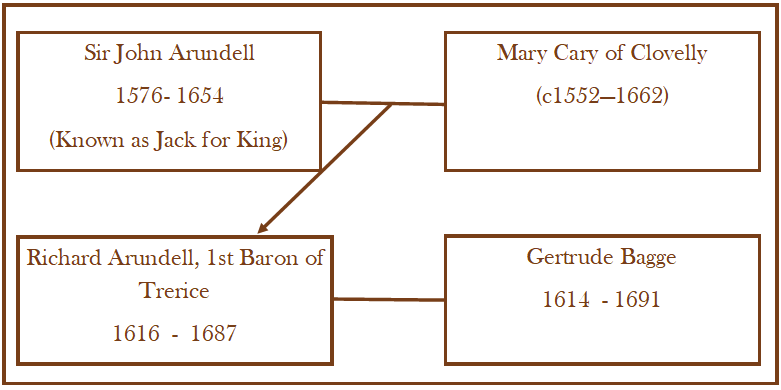

(The family tree shown will help to follow the first three family members who set in place the acquisitions of Trerice and Ebbingford and other linked estates.)

The Arundells acquired Trerice in the mid-fourteenth century when Ralph Arundell married Jane Trerise, the sole heiress of Michael de Trerice and his wife Alice de Flamock, who was the daughter of Lord Flamock or Flamoke.

Ralph was succeeded at his death (c1369) by his son Nicholas Arundell- who was apparently, still a minor. Nicholas married Elizabeth Pellor and their son, Sir John Arundell, married Jane Durant in the early fifteenth century and she brought him the manor of Ebbingford, at Bede’s Haven (Bude). The manor formed part of her dowry, and this would be their home for some time.

The son of Sir John and Jane Durant was yet another Nicholas, who married Johanna St John, and the couple had a son, also a Sir John Arundell (c1428-71).

This Sir John Arundell married Margaret Courtenay but the couple had no children, she died in 1458 and Sir John then married the much younger Anne Moyle (1440-1542).

We now start to have more career details and more background history. He evidently was a courtier as he was made a Knight of the Bath in 1465. However, Sir John eventually moved the family seat from Efford to Trerice, reputedly because he had been warned in a prophecy by a shepherd, who he convicted of an offence in his judicial capacity, that 'when upon the yellow sand, thou shall die by human hand'; so, he wanted to live further from the beach!

However, he did not escape his fate, for while Sheriff of Cornwall in 1471 he was ordered to recapture St. Michael's Mount (which the Earl of Oxford had seized for the Lancastrians), and in attempting this he was killed in a skirmish on the sands in Marazion Bay.

(The black and white picture is of Ebbingford dated 1896 )

Sir John’s heir to Trerice was still an infant at the time of his father’s demise. He was another John (c1470-1512) who, like his father he was made a Knight of the Bath. Unfortunately, he died fairly young at the age of 44, leaving as his heir Sir John Arundell (c1494-1561).

Sir John played a significant role in the Court of the day and in Cornish affairs as Vice-Admiral of the western seas and became active in combating threats from the French and Spanish invasion. He was also able to negotiate his way through the troubled waters of the Protestant and Catholic turbulence of the day. Somehow, suppressing those taking part in the Pilgrimage of Grace, which was against the Protestant reforms off Henry V 111, but later being asked by the Catholic Queen Mary to welcome King Phillip of Spain, should he find his way upon Cornish shores. So he had his feet in the camp of the day and got away with it.

Sir John (1494-1561) married twice; firstly, to Mary Beville of Gwarnack, near Truro and secondly to Juliana, the daughter of James Erisey. When he died in 1560 it triggered a protracted inheritance dispute which ran and ran. The only son of Sir John’s first marriage to Mary Beville was a Roger Arundell who is understood to have died around 1558, that is before that of his father. Without a lot of evidence, he is later said to have been insane, but he did leave an infant son, yet another John (1557-1613). This infant John should logically have inherited the estate of Trerice. However, this did not happen.

The early death of Roger Arundell left his father with the problem of whom to dispose of his estates. He may have thought the mental issues that his son Roger is said to have suffered, may have passed to the infant John, or he may have thought the lad was too young for such responsibility. Another interpretation, in the Parliamentary records, say the estate was initially left to the infant son, but child died.

There was yet a further consideration, Sir John had a further son, Robert Arundell (c1528- 1580), with his second wife, however, it is said that this was before they were married, and Robert was therefore legally illegitimate. (The Parliamentary History records dispute this interpretation as the words used to describe the position of the child in the family could have a different meaning.)

The net result is that Sir John decided to settle the estates of Trerice and Ebbingford in the hands of his eldest legitimate son of his second marriage, which is the Sir John that did so much for Bede’s Haven, Bude (1533-1580). This Sir John may have been something of a favourite son and this may have influenced this inheritance choice.

There were other provisions in this will, which left his young grandson the estate at Gwarnack and to the “illegitimate”, Roger Arundell the estate of Menadarva, at Camborne. Roger appears to have accepted Menadarva, but the young John Arundell felt deprived of his rightful inheritance of Trerice, as he saw it, and he actively tried to recover this birth right over many years.

So, we can now explore the life of (our Bude) Sir John Arundell of 1533-1580. He appears to have been a kind and considerate person and a family man for whom public office was a duty to be observed, rather than a career to embrace- in other words, he did what was expected of him but maybe life and family were a little more important. Sir John was therefore disposed to resolving these inheritance issues and he made various attempts to do so. And by 1570-73, he felt he had succeeded in doing so. We now see him directing his attention to rebuilding and updating the estate at Trerice.

Sir John had married Catherine Cosworth with whom he had daughter Juliana, but Catherine died June 1572, probably at Trerice. (See family tree above) Sir John then married Gertrude Denys March 1st, 1573, in London. They then spent quite a lot of their time at Ebbingford, although their five children are recorded as being born at Trerice.

When Sir John and Lady Gertrude arrived at Bude, their manor was only accessible from a track on the south side of the estuary from Helebridge; to cross to, or from, the north side was a game of chance, across what was a tidal waterway- that is only when the tide was ebbing, hence the name Efford or Ebbingford. The estuary did however offer a safe haven for trading ships further up the estuary and away from the main impact of storms.

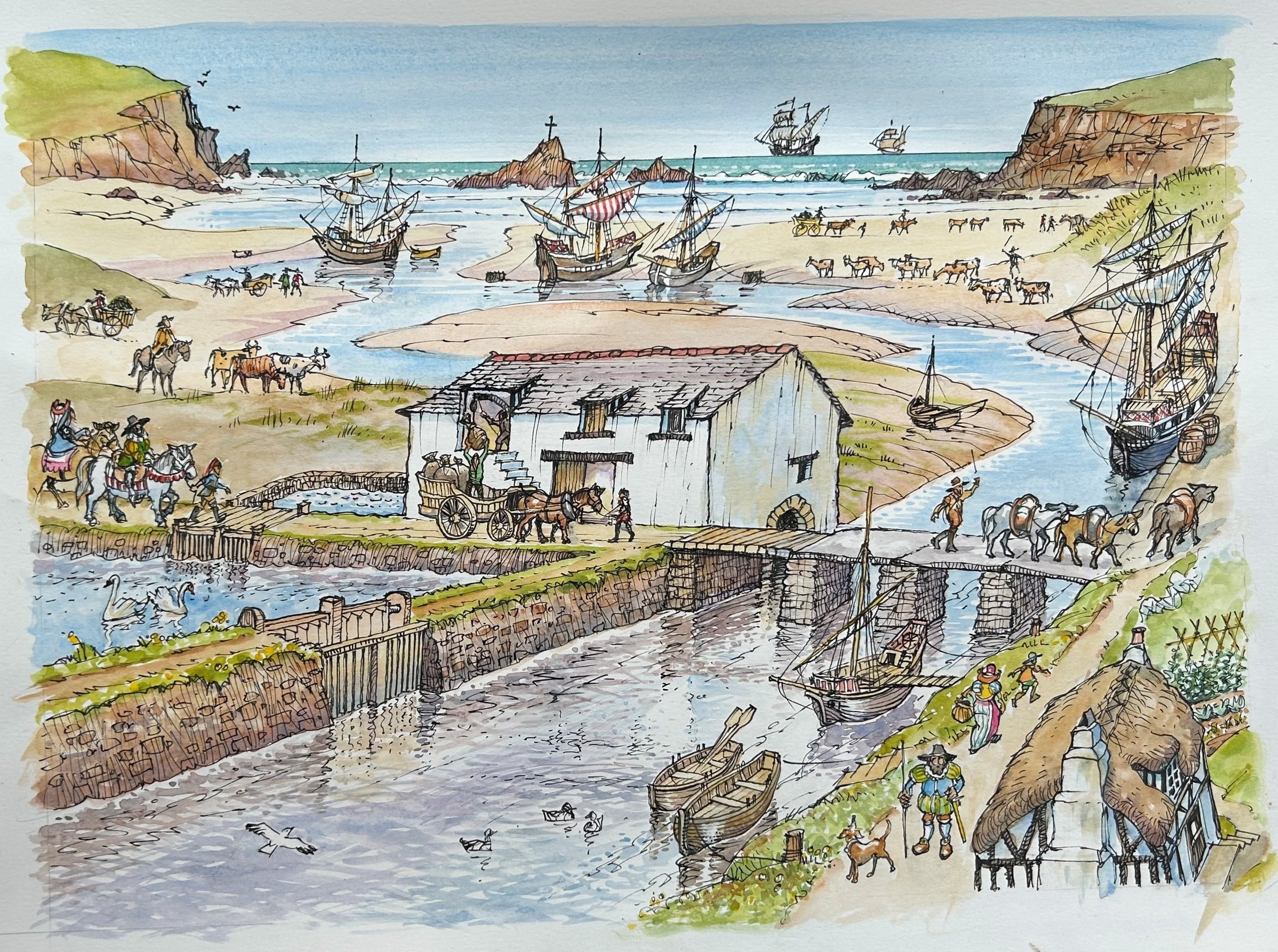

The picture is of a digitally altered image of the river Neet estuary at it would appear at time when Sir John Arundell came to live at Ebbingford.

In medieval times, corn grown by tenant farmers had to be milled at the Lord of the Manor’s mill and Sir John needed a mill near Ebbingford. But the area was unsuitable for traditional stream driven waterwheels, as there were no suitable rivers. He therefore set about creating a tidal mill which required a causeway and dam across much of the mouth of the estuary forming a millpond which was filled by the incoming tide. When the tide receded, or ebbed, gates were opened to allow the entrapped water to flow from the mill pond through the mill mechanism driving the millstones.

(See the image which forms the front page of the book, Bude’s Tide Mill and Bridge.)

The creation of the millpond and causeway greatly facilitated crossing the estuary for the local people. The mill was probably completed in 1577 but unfortunately Sir John died three years later in September, 1580 and his wife Lady Gertrude had to complete the crossing by building a small bridge to cross the narrow river at what we, today, call Nanny Moore’s Bridge; this was all that remained of the wide estuary and the building of the mill and dam almost certainly accelerated the silting of the estuary eastward to Helebridge.

This is an image specially commissioned to show what Bede’s Haven, would have looked like in 1577. Artist Harry McConville of Bude.

It is interesting at this stage in our story to look at the character of Sir John as this helps us understand why he was happy and content at Ebbingford. The History of Parliament website says:

“Sir John Arundell’s father had been a courtier and when he died in 1561, left his his three-year-old grandson John as heir to Trerice: this boy was not to enjoy his inheritance for long, and on his death the family property passed to his uncle and namesake.”

The uncle was, of course, Sir John Arundell and he, it is said, was a favourite son, and that doubtless contributed to his two appearances at Westminster during his father’s lifetime, although neither occurred while Sir John was sheriff of Mitchell 1553/4. The village of Mitchell was owned by Sir John’s kinsmen, the powerful Arundells of Lanherne, and until the accession of Elizabeth, that family’s support was a pre-requisite for election to such a position.

“In 1555 Sir John’s prospects were improved by a combination of circumstances: his namesake of Lanherne was returned for Preston; Sir John Arundell of Lanherne was sheriff, and a Cousin Richard Chamond was elected knight of the shire for Cornwall. Three years later John Arundell of Lanherne was to sit for the shire, and his promotion made way for (our Bude) Sir John’s re-election for Mitchell.

The History of Parliament records says:

“The Catholicism of the Arundells of Lanherne was distasteful to Elizabeth, and after 1558 their authority in Cornwall waned. It was perhaps for this reason, as much as for his being ‘a somewhat inarticulate man, who preferred to stay at home and superintend the building of Trerice’; i.e. that Sir John did not reappear in Parliament.”

Sir Richard Carew married Sir John’s daughter Julianna (by his first wife) in 1577 and he left a description of his father-in-law:

“Private respects ever with him gave place to the common good; as for frank, well-ordered and continual hospitality, he outwent all show of competence; spare but discreet of speech: better conceiving than delivering. Briefly, so accomplished in virtue, that those who for many years together waited in nearest place about him, and by his example learned to hate untruth, have often deeply protested how no curious observation of theirs could ever descry in him any one notorious vice”.

(Photo shows the modern Trerice Manor.)

These observations paint a picture of someone who was not suited to the cut and thrust of political life, but was, clearly, a thoroughly compassionate person who sought and preferred the peace of Cornwall rather than the drama and tumult of those dangerous times. We should also remember that when he married Gertrude Denys, she was just eighteen years old and could claim ancestry that included Lady Jane Grey and Queen Elizabeth 1st.

The extent of Sir John’s estates is apparent from his will; at his death in 1580 Sir John left his three-year-old son, John Arundell (1576-1654), the newly rebuilt seat of Trerice, over 2,000 acres in Cornwall, Devon, Somerset and Dorset, and a reversionary interest in a further 3,050 acres held by the Gwarnack branch of the family.

Sir John Arundell, as he became, was the second major figure in the family, and from an early age he showed signs of ability; he was first elected as an MP (for the local borough of Mitchell) shortly before coming of age in 1597, and he was already active in Cornish administration when he became MP for Cornwall four years later. Nevertheless, the inheritance issues that plagued his father’s life, remained a threat. After a great deal of legal activity most issues had been settled by 1622, but even then, Sir John remained uneasy, and in 1637 he paid £80 to forestall a possible claim on Trerice by the Prideaux family who had been bequeathed the estate at Gwarnack when (that) John Arundell died childless.

Sir John married Mary Cary of Clovelly and they had five children, four boys and one girl called Anne. The first two boys born to the couple were, Richard and John.

We now enter the period of the English Civil war and Sir John was now in his mid-60s, but he took up arms for the King alongside his four sons and, unfortunately his eldest son Richard died in the fighting. Being too old himself for service in the field, he was made Governor of Pendennis Castle, which he held for the King.

There were concerns that Sir John was too old to withstand the duties as Governor of Pendennis at a time of Civil War, but he proved them wrong. When the castle came under threat he proved resolute and on 18th March 1646, he answered Sir Thomas Fairfax’s summons to surrender with unflinching defiance.

He wrote to Sir Thomas: “I wonder you demand the castle without authority from His Majesty, which if I should render, I brand myself and my posterity with the indelible character of treason. And having taken less than two minutes resolution, I resolve that I will here bury myself before I deliver up this castle to such as fight against His Majesty, and that nothing you can threaten is formidable to me in respect of the loss of loyalty and conscience. In the event, Arundell surrendered on honourable terms after an epic five-month siege and he and his men had resorted to eating their own horses. But Pendennis was the last royalist stronghold in England to capitulate and it is said that the men were allowed to leave the castle still bearing their arms. Perhaps as a consequence of this loyalty, Sir John was ultimately know by the sobriquet, “Jack for King”.

However, with the overthrow of Charles 1st and Cromwell coming to power, the Arundell estates were seized by Parliament and were initially made over to one of his creditors, who allowed him to remain in occupation on easy terms, but Sir John was repeatedly arrested on suspicion of conspiracy. In March 1651 he and his son Richard were fined £10,000, though this sum was reduced to £2,000 in February 1654, and the full estates were only recovered by his heir, Richard Arundell (c.1616-87), after the Restoration.

There is a fascinating and slightly amusing account of life in the household of Sir John in October 1639 that is worth moving away from the direct story line. It suggests there may have been a little too much alcohol intake and a certain amount of pent-up rancour between Sir John and his nephew Cosworth. We should remember that Sir John’s mother was a Cosworth. The exchange below is an extract from what ultimately resulting in the issue being put before a commission headed by Sir Nicholas Slanning. The extract of the deposition follows in the words and spelling of the times:

Sir John Arundell accused his nephew, Cosworth, a trained band captain, of calling him 'a base cheating rascall' at his house in Trerice, Cornwall, in October 1639. Cosworth contended that he had spoken the words in 'a merry and pleasant way' and the following day had made a full apology, putting his action down to having been drunk. Since then, he claimed, he had been received at Arundell's house, with no sign of ill feeling. A commission, headed by Sir Nicholas Slanning, took depositions on Arundell's behalf at St Columb, Cornwall on 19 August 1640; but nothing further survives.

1. He confessed to be true.

2. He denied to be true 'in any parte further averring that in and since the months mentioned in the libel he hath oftentimes beene at the house of Mr Arundel of Trerise amongst companie and other persons of good qualitie and hath been there very friendly and courteously entertained; and Mr Arundell within the same time hath been at his house with persons of like qualitie and accepted of entertainment there, and that it did not at any time in either of those places appear to him or others then in company that Mr Arundell had conceived or retained any dislike or distaste against him by occasion of any such words as are pretended in the libel or otherwise.'

3. 'He believes what he hath affirmed and denies what he hath denyed.'

And so, it continued to disposition 6:

6. The next morning after the words were supposed to have been spoken did not Cosworth address himself to Mr Arundell in 'a very civell and humble manner, sayeinge I am told that I sayd wordes in your offence last night, but I do not remember I said any such words; yett I am hertely sorry if I sayd any such wordes'? 'Did not Mr Cosowarth therupon bowinge his knees even to the ground aske forgiveness of Mr Arundel'? 'And did not Mr Arundell saye that he did hartely forgive him, and therewithall take him by the hand, lead him into his cellar and seeme to be verie good friends'?

Sir John died in 1654 and did not live to see Charles 11 restored to the throne in 1660 and his next eldest son Richard inherited Trerice.

When King Charles II was restored to the throne a great many people felt they had a claim on his purse and patronage: all those families who had fought for the Royalist cause and sacrificed lives or been fined by Parliament; all those who had patiently financed the royal exile; and those who had engineered the Restoration. At the same time, Charles knew that in order to avoid re-igniting the Civil War there was a limit to the extent to which he could dispossess people who had purchased confiscated estates during the Commonwealth years, or fine Parliamentarian supporters, to meet these claims. As a consequence, most Royalists got little reward for their loyalty and little compensation for their losses. Against this background, the Arundells did better than most, allowing for the fact that their sacrifice had been greater than most and their loyalty constant.

Richard Arundell had been promised a peerage by Charles I in 1646 and this was delivered in 1665; he was made Baron 1st of Arundell of Trerice; and in redemption of another pledge, he was also restored to his father's Governorship of Pendennis Castle for life in 1662. He held positions at Court, including Master of the Horse to the dowager Queen Henrietta Maria, and he was also given cash; we know of a pension of £1,000 a year and a one-off payment of £3,000 in 1670, and a hostile pamphlet alleged a total of £20,000 in 'boons'. His younger brother Nicholas secured a lucrative position as farmer of the excise for Cornwall in 1662 but only enjoyed it for three years before he died in 1665. When Richard died in 1687 he was succeeded by his only son, John Arundell (1649-98), 2nd Baron Arundell of Trerice.

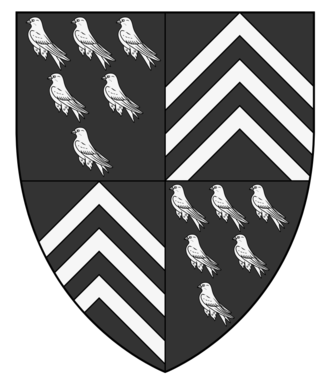

Shown are the Coat-of Arms of the family which are a combination of ancestral families:

House Arundell of Trerice

Lords of Carshayes, Trerice

and Lansladron

Barons Arundell of Trerice

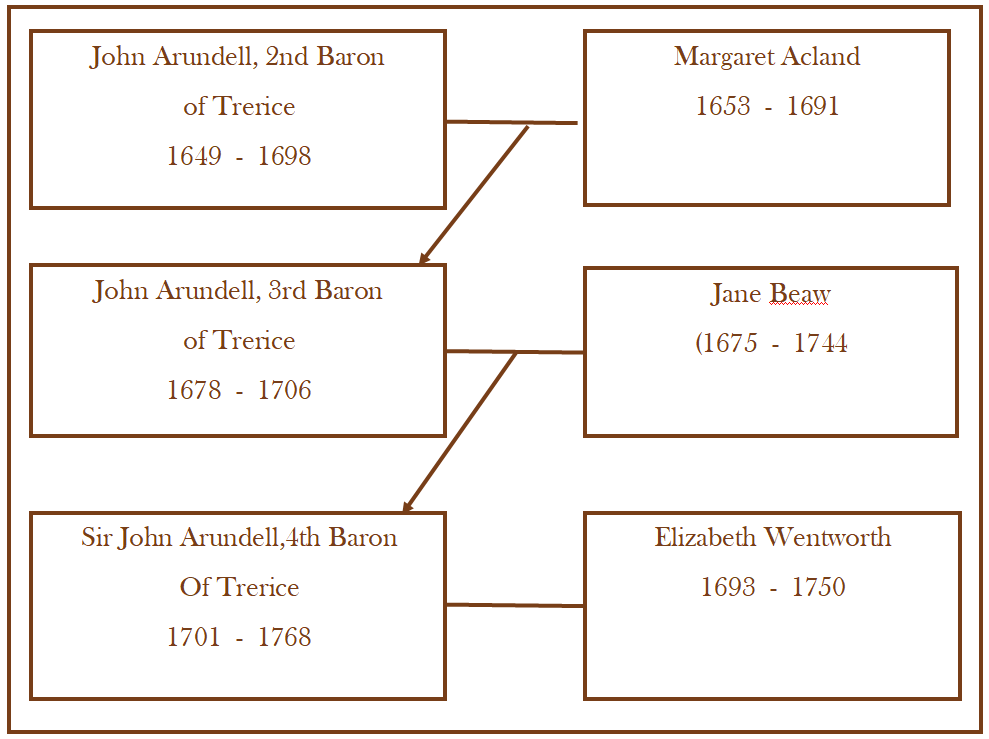

John Arundell, 2nd Baron Arundell of Trerice became an MP and then succeeded to the title Master of the Horse to another dowager, Queen Catherine of Braganza, 1687-94. In 1675 he married Margaret Acland of Columb John (Devon), who brought him a dowry of £8,000. Although she died in 1691, it was as a result of this marriage that the Trerice and Efford estates passed in 1802 to the Acland family.

The 2nd Baron and Margaret Acland had two sons, of whom the younger, Richard Arundell (1696-1758), was clearly a chip off the old block and went on to make a good deal of money from Court and public appointments, and to have the same sort of reputation for being beloved of his friends as his great-great-grandfather, almost 200 years earlier. The elder son, John Arundell (1678-1706), 3rd Baron Arundell of Trerice, who inherited the title and estates in Cornwall, was less obviously in the family tradition. He died very young, at 28, but had shown by then no sign of taking on a role in public life. He did marry and produce a son, but when he died, he required that he should be buried in the clothes he died in and forbade anyone to uncover his body between his death and burial, which somehow suggests morbid preoccupations.

His only son and heir, John Arundell (1701-68), 4th Baron Arundell, was just four when his father died, and may later have been estranged from his mother. Some sources refer to him as the "Wicked Lord Arundell" because of a story that a female servant at Trerice committed suicide after he had debauched her and then abandoned her when he discovered she was pregnant. In 1721, when it was fairly clear that his uncle Richard would not produce any male heirs and that producing an heir to the title and estates was therefore down to him, he married a woman twenty years his senior who was at the very end of her childbearing years, and they did indeed have no children. His motivation may have been financial, as she was a considerable heiress, but most 18th century peers would probably have put lineage before lucre. Some of the funds she brought him were invested in landscaping works at Trerice, but the couple seem to have lived mostly at Henbury House, Sturminster Marshall (Dorset) which they either acquired or inherited; certainly they were both buried at Sturminster Marshall rather than at Newlyn East, the traditional burying-place of the Arundells of Trerice.

On the 4th Baron's death in 1768 his estates all passed, under a clause in his marriage settlement, to his wife's nephew, William Wentworth (d. 1775). William let Trerice, which became a farmhouse and began its long descent into semi-dereliction. The Wentworths are shown as owners of Ebbingford manor from 1768 to 1802 and it is possible that they had little interest in maintaining the tidal mill. This may have been when the mill fell into disrepair.

Eventually, William's son and daughter inherited the estates in turn, but in 1802 they passed, as we have seen, to the Aclands at Killerton, who already possessed much larger and grander properties scattered across Devon and Somerset. They had little use for Trerice (although the hall there seems to have been restored in the 1840s to provide a suitable setting for occasional manor courts and tenant feasts), but the Efford estate, it is said, offered some development possibilities and this challenge was taken up enthusiastically by Sir Thomas Acland. He completed the building of the Bude Canal in 1823 and was generally a benevolent landlord who had a real interest in the town of Bude and led to the town we know today. The Aclands remained at Ebbingford until 1861.

Early Ebbingford Families

We do not know who may have built a home at Ebbingford in very early times but it will have offered early settlers a sheltered location at the edge of the estuary with access to the sea.

However, England has an almost unbroken series of monarchical accounts, or financial records, into medieval affairs going back to 1129-1130. They are known as the “Pipe Rolls”. In those of 1194-5 an entry says, Henry Heritz renders account to the Earl Robert Mortain 40 marks having seisin of the manor of Ebbeford (Ebbingford) which is adjudged to be his by service and hereditary right”.

This “service” was to provide a guard for the Kernell of Launceston Castle in time of war.

The choice of words in this document suggests that there was a property, or manor, here already, of which to take possession- possibly in the times of King Harold.

There are also records of this time in the Blanchminster Trust records that document Lucy Turet, who married into the Blanchminster family, giving permission to this Heritz family to construct a track or road leading to Ebbingford- where there were lime kilns. The Heritz family lived at the Manor until around 1300 when it became the possession of the Waumfords of Whitleigh, near Halwill, Devon. The property then passed from the Waumfords by a coheiress to the Durants and, as we saw earlier, the heiress of the latter brought it to the Arundells of Trerice: Ebbingford then passed, with the Trerice estate, to Sir Thomas Dyke Acland, in 1802. During this period, part of the old mansion was occupied as a farm-house, and part as the occasional residence of Wrey L'Ans, Esq.

When Leland was in Cornwall in the reign of Henry VIII, Efford was the residence of Sir John Chamond, who had married the mother of John Arundell, then of Trerice, and widow of Sir John Arundell, the brave naval officer.

In 1861 it was given to the Commissioners of the Church as a vicarage by the Aclands. There then followed a succession of occupants, presumably associated with the church until in 1953. The property was then exchanged for a house at 8 Falcon Terrace, by Sir Dudley Stamp C.B.E. The Dudley Stamps have owned Ebbingford since that exchange.