Duckpool, Coombe Valley & Stowe Woods- A Valley History Lost in Time

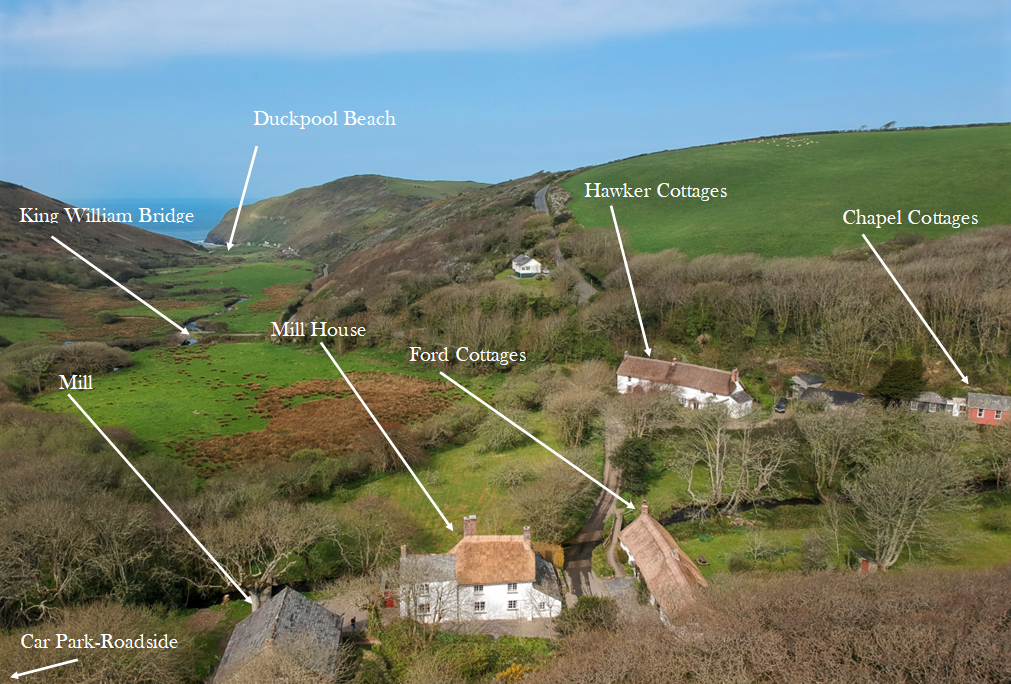

The picture shows Duckpool as seen from the south approach cliff path.

This is such a special place that it needs a little explaining before setting out to discover all that the valley has to offer.

The problem is that on first appearances it looks as if nothing has every happened here- nothing could be farther from the truth.

First we must explain the place names within the valley; at the seaward end we have Duckpool Beach and the duck pool; a kilometre or so up the valley is the small village of Coombe; a little to the south of the valley, on the Stibb road, is the site of the great mansion of the Grenville family- now dismantled; heading up the valley from Coombe are Stowe Woods. Within the woods is an Iron Age village or Cornish Round; at the head of the valley is the dramatic location of a medieval castle. If you continuing further up the valley you will arrive at the very old street town of Kilkhampton.

The whole valley is completely unspoilt and peaceful, in the extreme; please help us to keep it that way.

And an advance warning here, if you decide to visit the “Cornish Round” in Stowe Woods, discussed later, take care, and ensure you leave it as you find it.

This image has been chosen as it conveys the mystery that you will enjoy within Stowe Woods; “its meaning, the woods of the church”.

History Within:

Here again it is necessary to summarise all that is hidden and represents history lost in time.

In the very long distant past during the last Ice Age, the sea was out of sight and early travellers could walk along what is now our beach, no doubt hunting in the valleys along our coast.

In the Romano-British time our coast was a major trade highway and here at Duckpool (then a small harbour) was a small industry producing metal ware for the people of the valley and the village, manors and castle of Kilkhampton.

A little up the valley away from the sea is the small village of Coombe. The mansion of the Grenville family has already been mentioned, but within these woods they cut the bark from the oak trees, processed and transported it to Ireland for use in the leather tannin industry. (That is from the Port of Bude) The Grenvilles also operated at least one corn mill in the valley.

Continued next page:

Image is typical of the walk within the wood and continuing the history within the Coombe:

Leading from the village of Coombe is the Stowe Wood walk; this path is modern. The walk that the famous Parson Hawker took and “sat beneath an oak” to write the (Cornish Anthem) ballad, “The Song of the Western Men”, this path is just visible as a sunken clearing to the right valley side of the modern path.

Half-way up the valley and set upon a southern spur within the wood, is an early Iron Age Village or Cornish Round.

Continuing up the valley will take you through a few fields and holiday farm cottages; beyond which and set prominently upon another spur, is the medieval castle.

Looking down on the duck pools from the north cliff.

Duckpool or Duck Pool?

The story should start with the names of Duckpool and Coombe.

The name Duckpool in folklore gives its origins as the “ducking pool” – of witches! The true meaning is rather more prosaic, it’s where there was a pool in which there were often wild ducks! First recorded in the sixteenth century by the Cartographer John Norden as Duck Poole. However, in a map based on his early work, dated 1610, shows our little beach as Duckpool.

Coombe Hamlet or Dell; picture courtesy of Landmark Trust.

Coombe or Cûm

Coombe Valley comprises, Duckpool, Coombe and Stowe Woods. The little hamlet of Coombe sits at the heart of the valley. Coombe may derive from the Cornish name of Cûm which means dingle or dell - little wooded area; often romantically compounded to dingley-dell – Charles Dickens, Pickwick Papers (1836). This really is wonderful valley with enchanting woods just inland.

Start of our Walk

There is so much to discover in this valley that it has been decided to cover the story in two parts. The first part will end with the Iron Age “Round” village up in the woods. The second part will start at the medieval castle at the head of the valley at Kilkhampton. (See Menu, Our Walks and select Kilkhampton Medieval Castle.)

If you have a head for heights, start the discovery walk from a little way up the cliffs on the north side of the valley. Looking eastward up the valley we see a scene that we could imagine has been unchanged by time. This would be a misconception.

The form of the valley floor is always changing as the river cuts new meanders on its path to the sea; the profile of the beach head changes with each storm and the beach itself will be sandy or rocky according to the prevailing winds.

History Notes

Minor beach and valley changes are insignificant to the changes that have taken place here over greater periods of time which reflect a truth about our whole coastal bay; it is all vastly changed. The coastline during the last great Ice Age was in fact land. At least 26,000 years ago, early hunter-gatherer groups made their way on foot past this valley, along what is now our shoreline, following their prey. We know one of their number died just a short distance to our north across what is now the Bristol Channel, in Pembrokeshire. This is the famous Red “Lady”, found in the Paviland Cave; the Lady was, however, later proven to be a male aged around twenty-five to thirty. His party had followed their prey during the summer period as far north as they could go before meeting the face of the great ice sheets of the last great Ice Age.

It is hard to image but 26,000 years ago, sea levels were around 120-150 metres lower than present day and the shoreline would then have been at the present Continental Shelf. Another quirk of crustal deformation is that the land locally had also risen, ironically due to the compressive forces of the Ice sheet farther north.

Note: Your attention is drawn to the location just to the right of the camping car in this picture. This area is where a Romano-British industrial metal working site was discovered - discussed on the next pages.

A Shipping Highway and Harbour

We can now begin to imagine the scene here during the Iron Age, perhaps in the year 700 BC. The sea has now reclaimed much of the land, but the cliff-line is around 300 metres westward and the land itself is now sinking- as it continues to do today. The Celtic sea, at that time, was a major highway for trading and movement of people all along the western seaboard, connecting lands northward along our coast to the Irish Sea, to Wales, Ireland and Scotland and southward right down the western Atlantic to the Mediterranean.

Duckpool was then a small harbour trading point for the immediate hinterland communities and, recently discovered, much more.

Archaeological studies have revealed early buildings here where people lived and worked. The exact nature of the first community here in late Bronze Age and early Iron Age has yet to be established. But, in 1983 a local historian, Richard Heard, started making discoveries that alerted archaeologists to this location having a much bigger function in the Romano-British period.

An initial investigation was carried out in 1992 and a further more detailed study conducted in 2017 . This revealed evidence of an industrial site, where there was lead casting and reworking of raw metals of copper, pewter, and iron.

The Phoenician Mediterranean; from Phillip Beale’s book, Atlantic B.C.

Phoenician Legacy?

There is still more of intrigue at this remote spot, as this same community was engaged in producing the rare and expensive purple dye that coloured the clothes of Emperors and Kings. This is known as Tyrian Purple; a process discovered by the Phoenicians of Tyre in the eastern Mediterranean, or Levant. This involved a complex process using Dog Whelks. There is much to suggest the Phoenicians were trading directly or indirectly along our coastline and we must assume that this trade brought the people of this very small community into a trade agreement to produce and sell this dye to the traders. It is difficult to understand how these people would otherwise have learnt to produce this dye, or have a need for the product, if it were not for use in a trade. The Phoenicians had established a trading point at Cadiz from around 980BC, from where they dominated trade along the Atlantic facing territories, which included the Celtic and Irish Sea areas. So, this would suggest activity here at a very early age.

Romano-British Times

Radiocarbon dates and artefactual evidence identified by the 2017 study, suggests that the beachhead continued to be used as an industrial site between the seventh and twelfth centuries AD, although metalworking had by then ceased. However, in can be said that the harbour and industrial site was probably serving the needs of the prosperous early medieval manor of Kilkhampton for some considerable time.

For much of this early period, the community of Duckpool probably lived in a village “Round” nestled within Stowe Woods - discussed later.

The Romans did not have much influence in our area, but it is thought that a few miles along the cliffs to the north there was a Roman signal station used to keep an eye on shipping heading towards the Bristol Channel and South Wales. (Or was a station to spot marauding Irish, Vikings and Scottish Picts later in the Roman period?) There was a second Roman signal station to our south, at St Gennys. And, at Kilkhampton, there is evidence of Roman foundations of some kind and Roman coins have been found locally; so, there was a Roman presence here, if not one of dominance.

Our walk now moves eastward up the valley to the hamlet of Coombe where the story continues to be one of change.

Parking Note: You can leave your car at Duckpool and walk to the junction with the main road. At the junction, turn left, walk a short distance up the hill and turn in to the short road on the right. You then arrive at the ford (See picture opposite) and the hamlet of a few houses and the mill.

Alternatively, take the car to the junction, turn right, drive over the bridge and very soon there is parking for a number of cars at the roadside. See the picture below.

If you have chosen to drive the car from Duckpool, this is the parking space for the hamlet of Coombe. At this end of the parking, as viewed here, there is a small path leading over a bridge to a beautiful glade. The mill is in front of you and the mill house alongside. There are only a few houses here, but do not forget to cross the bridge over the ford to see Hawker’s Cottage.

The Hamlet

The first mention of this hamlet, in the written record, is 1520 but we know that this clearly had been an active settlement deep into pre-history.

If you have read the story of the Bude harbour you will remember that the estuary was divided between two great families and, so it is here at Coombe. The land to the west of the stream was in the ownership of the Duchy of Cornwall; that to the east, initially in the ownership of the Cobblestone family, until the Elizabethan period, when it passed to an even greater aristocratic family, the Grenvilles of Stowe -more of whom shortly.

There are just a few houses here today but in the early 19th century there were 12 or 15 houses.

The community reflects the changing of lifestyles and attitudes to such isolated localities that play out to this day.

In the early 19th century, it was very much a hard-working community of farm labourers, millers, carpenters, and blacksmiths. As the century progressed it was beginning to attract the attention of the leisure classes who asked the local inhabitants if they could join them in their homes for a week or two just to experience the peace and quiet. Soon they would come to live.

The famous Parson Hawker came to live here in 1820s. (See a separate article on Parson Hawker.) The Tape family, longtime residents here, developed part of their house as a tearoom from around 1914 until 1966, when the Landmark Trust bought a number of the houses over the next few years. Most of the houses we will visit are in their care today as holiday lets.

The Great House of Grenville

Having parked your car, you should be aware of even greater change here in this quiet hamlet. Between 1676 and 1679 John Grenville, Earl of Bath, built The Great House of Stowe on the south bank of the valley. This was said to be one of the five great houses of Cornwall. “The Great House”, however, proved to be too grand and expensive to run and it was eventually demolished. But the Grenvilles continued live here for 600 years, and three members of the family brought fame to the name and to Stowe. Sir Roger Grenville was Captain of the Mary Rose when the ship sank in the Solent, his son Admiral Sir Richard commanded the Azores fleet under Lord Thomas Howard and was killed on board the Revenge when fighting against the Spanish in September 1591. And his son, Sir Bevill Grenville fought in the Royalist Army during the Civil War and played a significant role to win a battle, almost in his back garden, in May 1643 at nearby Stamford Hill – only to die a few weeks later at the battle of Lansdowne, near Bath. At the restoration Sir Bevill’s surviving son John was made Early of Bath – a reward for helping to restore Charles 11 to the throne. (See The Grenville Family from the menu.)

All that remains today of the great house, which can be seen on the right as you drive down to the valley from Stibb Cross, are these buildings created out of the old stables. On the road side is a large stone wall that surrounds the site.

After so much drama and change, we will now walk around the main houses of the hamlet and the old mill.

We now start our tour of the hamlet.

The King William Bridge

The bridge over the head of the stream at Coombe has the intriguing inscription, "Toward the erection of this bridge, built by subscription, in the year of human redemption 1836, his most

gracious Majesty King William the Fourth gave the sum of Twenty Pounds. Fear God!

Honour the King!"

The Reverend Robert Stephen Hawker of Morwenstow, as one of his first acts in the parish, had written to the King asking him to contribute towards the cost of building this bridge. The previous crossing offered no protection at times of flood, and it was a danger to local people and animals had been washed away at times. The build date fits perfectly with this being an early intervention by Hawker as he and his first wife Charlotte moved to Morwenstow in 1835. The couple rented the property that is today known as Hawker’s Cottage as a temporary home.

Hawker is said to have contributed some of his own money. In fact, his second wife later writes that it was largely financed by him; however, local author Joan Rendell in her book, Hawker Country (1980), contends that his contribution was £2.00. The present bridge replaced an earlier simple structure that was prone to flooding.

An early travel writer saw the view towards the sea from the bridge and wrote, “Coombe is an ideal spot, with its picturesque cottage and mill, and the wooded slopes rising overhead. Where the trout stream brawls seawards the marshy meadows are, in early summer, golden with irises. Half-a-mile onwards a break in the cliffs shows a triangle of sparkling sea, and no effect can be more remarkable than the view of dancing waves seen across a foreground of irises”. Clearly this writer was smitten with the beauty of the seaward view from the Coombe village.

Opposite is the same scene, completely unchanged from when the above was written.

The Mill Overshoot Wheel

There has been a mill at Coombe since at least 1694 and probably long before that, although the present one dates from 1842. Coombe is an obvious place for a mill having a water source from the higher ground to the north. This enables the creation of a leat conducting water to the top of an overshoot water wheel. This is the most effective of all the wheel types providing maximum use of the weight of water and gravity.

Feudal Life

The community of Kilkhampton is just a few miles up the valley and the feudal landowners would certainly have wanted to build and operate a mill here. During medieval times, when a serf used the mill for grinding wheat, he had to pay a certain amount to the lord of the manor. This charge was known as “banalities” and was basically a fee imposed by the feudal lord for the use of his mill. The profession of a medieval miller was one of the most common professions during medieval times as there was a mill in every village. Compared to ordinary peasants a medieval miller was generally well off. Milling required a lot of skill and the miller normally produced a range of products other than simply corn flour.

The miller would usually pay the Lord of the Manor a fee to be able to use the mill. The miller could then make his own bread by grinding wheat using a quern stone which he could then sell to the people of a medieval village, and he too levied a charge for his services.

In time, the “banalities” charge took on a more legal term connected with the word Soke of Sac. The charge levied became the “Milling Soke” and as such was a legal obligation. This gave the landowners exclusive right to compel their agricultural tenants to bring their grain to the manorial mill. The miller took a toll, the milling soke, as a share or quantity of the flour produced - usually one sixteenth of the output. However, many millers were accused of taking an excessive toll usually for personal gain, resulting in a mistrust of some millers. Needless to say, this whole set up was very unpopular and proved difficult to enforce in such small communities as would have existed at Coombe – the Miller had to live in the community after all.

The mill of 1694 was probably part of the manor of Leigh (or Lee), but later becoming the possession of the Stowe Manor. The present mill has a build date stone of 1842, but a Tithe Map of 1840 does show the outline of what look like a mill here.

The present mill has three floors, linked by ladders and trap doors. On the ground floor, which is paved in slate, is the gearing for the machinery driven by the wheel on the outside. On the first floor are the millstones, a pair of French Buhr stones and also a pair of Cornish granite stones, placed beneath the grain hoppers. French stones were preferred as they were harder and of white stone- which meant that the stone impurities did not show up in the flour!

On the second floor are dressing and bolting machines. These bolting or boulting machines cleaned the impurities from the floor. The top floor received the corn from the farmer who may have already dried the corn - if not the corn was dried on this floor before milling. The process was then one of using gravity to supply the corn down through the floors, ultimately arriving through the hopers to the grinding stone, from where the flour dropped another floor ready for use as a finished product. Some mills also had further filtering at the final stage to remove the courser grain elements.

We now look at the history of the early houses at Coombe.

The Mill House

As we have seen, the miller was fairly well off financially and in all communities could command a reasonable house. The earliest parts of the mill house with its thick walls and thatched roof, dates from a little before 1700 – probably the building shown on a map of 1694. The slate roofed part of the building looks like an addition, possibly dating around 1800.

Like the other early writer quoted above, Charles Kingsley was also smitten with Coombe and readers of Westward Ho! Will remember that in his novel of 1855 he has heroine Rose Salterne sent to Coombe Mill to be out of the way of her numerous lovers.

The interior plan, according to the Landmark Trust, who now own the property, is typical of small farmhouses in remote areas such as this, being basically a continuation of Tudor arrangements. That is, just one room deep, it had two ground floor rooms, a main room with wide fireplace on the back wall and an inner room, also with a small fireplace. The tenant of the mill in the 1840 Tithe Survey, with orchards, garden and two meadows along the stream of Coombe Valley, is a Mary Lashbrook, who was described in a census of the following year as a miller, aged 70. She lived here with her servant, Elizabeth Vanstone, and William and Richard Vanstone – aged 15 and 9 years. There are still Lashbrook and Vanstone families living in the area.

Then ten year later, in 1851, the mill was taken over by a new, younger miller, William Wood, aged 24. It is possible that possibly William’s father James ran a second Lee mill nearer Kilkhampton.

The Ford Cottage

This cottage is quite large, long and low in profile and the Ford still passes just to the west of the house. Its upper floor being little more than a loft. It dates from the middle of the 17th century. It has been much altered by time and has been in many usages.

Soon after 1914, a tearoom was run from one end of the cottage, which continued until ownership change to the Landmark Trust in 1966.

An early travel writer asked the then owners if he could spend Christmas with the family, this they agreed to do. The writer was T. F. Clarke and he wrote an account of his stay: activate the link at the end of the walk to, “A West Country Christmas”.

The Carpenter’s Shop

This property also appears on the Tithe Map of 1840 on land belonging to John Tape, a carpenter then living at Ford Cottage. (The Tapes lived in Coombe for generations, the last leaving in 1968) The building was used as a store for some years but was becoming derelict by the time the Landmark Trust acquired the property.

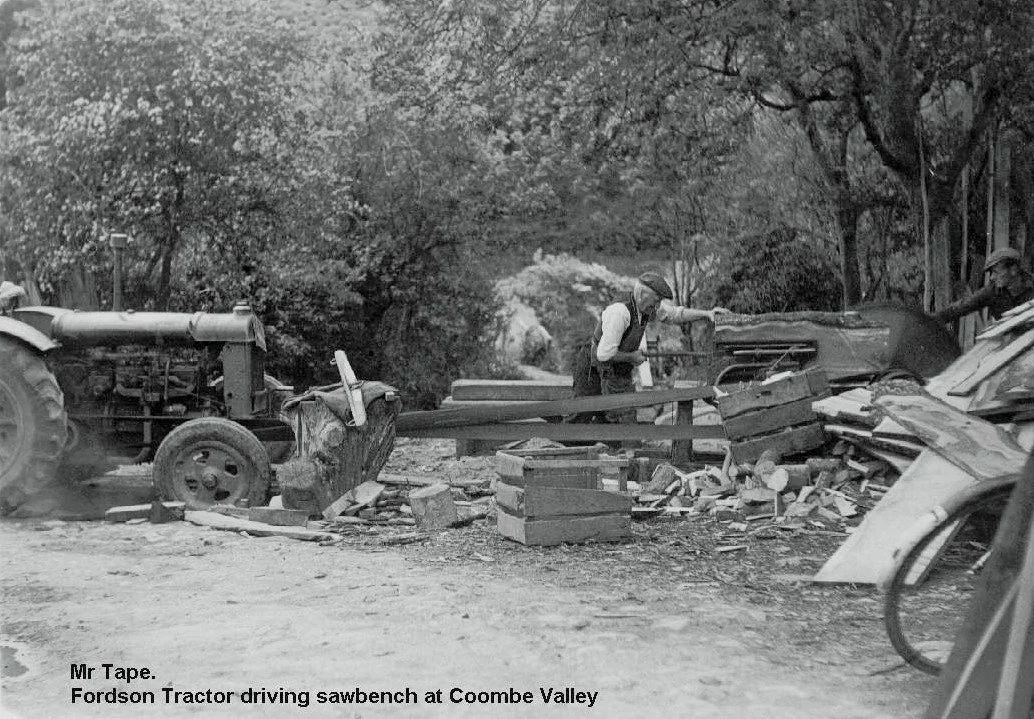

An early photograph -probably one of the Tape family using the power of the millwheel to drive a rotary saw.

And, opposite, a later picture with a member of the Tape family using a Fordson Tractor to drive a rotary saw – possibly now at his Carpenter’s Shop.

The Landmark Trust found evidence in one of their cottages to suggest the Tapes were also wheelwrights, with forging facilities on the sitting room floor of one of their cottages. According to tradition, long boats were also made here at the workshop.

Hawker’s Cottage

It was mentioned earlier that Coombe attracted many well-to-do families and for a while in the 1920’s Parson Hawker is said to have rented the property.

Clearly the property formed two houses at one time but apparently has been a single dwelling for most of its history. The main property dates from around the mid-17th century, however, one part of the cottage is thought to date from the mid to late 18th century. It had a succession of tenants through the 19th century- including members of the (Carpenter) Tape family. According to the Landmark Trust, the walls are two feet thick and include a bread oven, no doubt using flour from the mill. The living area appears to have been on the first floor with a workshop or even a byre on the ground floor in its early days.

Hawker married Charlotte L’Ans on 6th November 1823 and the couple may have spent some time at the cottage around 1825. Hawker says that he composed his famous Trelawny ballad, “Song of the Western Men” at this time while sitting under a staghorned oak in Sir Bevill’s Walk in Stowe wood. He returns to live here with his wife at this cottage in 1835 while his vicarage is being designed and built alongside his church at Morwenstow. Building work on the vicarage began in 1837. The cross-shaped window above the porch was inserted by him. (See picture.)

The Chapel

A Bible Christian chapel is marked on the Ordnance Survey map of Coombe in 1885, but for how long it had then existed is not entirely clear. This intimacy of this small building would have appealed to the local community and would have contrasted greatly with the grandness of the English church.

Wesleyan preaching was introduced to the people of Cornwall in the middle of the eighteenth century and, over the next century Methodism would become the main religion of the county.

Charles and John Wesley first came to Cornwall in 1743 as evangelists and their message directly related to the poor of the county who had become disillusioned with the excesses of the Church of England. Methodism would eventually attract the middle classes who actively supported the religion financially and helped it to grow in popularity.

The religion came in two forms, pure Wesleyan or its Cornish offshoot, Bible Christian, known as Bryanite after its founder, in 1815, William Bryan of Luxulyan. The strongly revivalist and ecstatic Bryanite preachers appealed to the Cornish poor, giving them a sense of purpose and brotherhood; and horrified the established clergy.

The Landmark Trust has a full account of Methodism in this area. Also, there is a link to Landmark properties available for renting.

Bevill’s Walk

We now start our walk along the woods leading to the Iron Age community village “Round”; the walk starts at the narrow path beside the mill house, just beyond the ford. See opposite.

The woods are enjoyable in themselves, but remember, the walk up to the fort does involve a short section that is a bit of a scramble and is suitable only for the sure-footed. The following pages will guide you there.

The Iron Age “Round” is actually nestled on a spur of land out of site to all within the woods. Whether you are seriously interested in this period of history or in such structures, it is still worth the scramble up through the woods to experience this peaceful and mysterious 2,400-year-old village.

Follow the path for a few minutes which will bring to the gate; pass through and continue to the right fork.

Ten or twelve minutes into your walk you take the right hand path, which curves around to a small bridge. Pass over the bridge and walk a further three minutes to the next fork shown on the following page.

A few minutes beyond the bridge take the left fork up a narrower path; walk up that new path for a further three minutes to the next fork.

This is your final fork left and you now walk three minutes up this narrow path to a tree stump, which marks the left turn to your short scramble up to the path in the woods - this leads to the fort itself.

This was the scene, July 2023 when there was a tree stump at the point of the left turn, up the banking and a few yards beyond is a path in the woods themselves.

Follow this path in the woods until it levels out; after only a very short walk bear around to your left and walk down the ridge top towards the fort itself. You may see wooden shacks left by individuals who have partied here at times.

As you walk down the ridge you will soon encounter the fort banking and it is a question of exploring the fort, being always aware of the footing and conscious of the drop-off in places - especially if young people are in the party. When you finish exploring return back down through the woods to the main path.

The “Rounds” tend to date from the later Iron Age through to the early post-Roman period. They are found widely in Cornwall with equally large variations in their siting. They are typically circular or oval, have a single earth and rubble bank and an outer ditch, with one entrance passing through the banking. They are in effect small communities set in a secure enclosure. Being situated in the woods the houses were probably of wood and turf, with stones being used for paved or cobbled entrances and possibly as part of the banking structure.

This is a section of the banking around the fort.

Rounds were replaced by unenclosed settlement types by the 7th century AD. Over 750 Rounds are recorded in the British Isles, occurring in areas bordering the Irish Seas, but confined in England to southwest Devon and especially Cornwall. Few of the Cornish Rounds have been studied in details and there is much yet to be learnt from such studies.

Some Rounds have evidence of small-scale metal working and given that Duckpool is now known to have been involved in metal work, then it is perfectly possible that some work was done here, as well as at the main site farther down the valley. It is difficult to see that this community was involved in much agricultural activity, but they could have had some pigs scavenging in the woods and other small-scale husbandry. But, as this was an important metal working community, maybe their products were traded for agricultural produce.

A further section of banking and ditch.

The Stowe Round is approximately 45m in diameter and has banking around 1.7m high above a ditch which is between 3m and 6m wide. The ground falls away steeply, other than a possible causewayed entrances from the north and south.

Care should be taken when exploring the village, especially when younger children are involved, as the escarpment falls away seriously on most sides.

As has been said, this site has not been studied in detail and development on the site has not been dated. However, the main fortification may have taken place towards the end of the Roman period 410AD.

As the Roman power waned so raiding parties came into eastern England from northern Europe but here in the west, bordering the Irish Sea, the Irish, the Vikings, and even Picts of south west Scotland were raiding Cornwall and Wales. Cornish numbers had also diminished as many Cornish men had left the County to fight with the Romans in Brittany and Gaul.

See historical note below.

When you come off the woods, back to the tree stump, turn right down the path, walk three minutes and take a further right. After a few minutes you will arrive at the image opposite. Here you have a chance of turning right back to the small bridge that you passed on your way in and you can then return on the path you came in back to Coombe. Alternatively, you can turn left at this junction and that will take you back to the main road and the steep hill that takes you down to where you probably left your car.

The second part of this walk takes you to the eastern head of Stowe Wood Valley where there are the remains of a castle that dates at least to the first civil war between Empress Matilda and King Stephen of England (1139-1153).

The walk actually starts just to the west of Kilkhampton on the A39. Drive back to the village of Stibb, pass straight through and follow the road to Kilkhampton.

Kilkhampton is a village steeped in history and has some good pubs to enjoy lunch before walking it off around the castle and around Kilkhampton Common- all highly recommended.

From the castle Motte you really have a spectacular view down the whole valley to Coombe and Duckpool.

For details, select Menu, Our Walks and select Kilkhampton Medieval Castle.

Historical Note to the Iron Age Village

After the year 360AD, raiders from Ireland are frequently mentioned by Roman historians. Irish poems credit the high king of Ireland, Niall, with having lead seven successful raids against Britain. The reward for success would have been precious metals, cattle and slaves. One famous British slave was St Patrick. He was captured by an Irish raiding party and taken to Ireland where he was sold as a slave. He there spent six years as a herdsman before escaping to Brittany on a trading vessel. He eventually found his way back to Britain to re-join his family but “voices” called him back to Ireland to convert the people to Christianity.

A West Country Christmas

We hope you enjoyed this walk. You can now use the links below to read the account of “A West Country Christmas” - which is highly recommended.

https://www.pathwaysofdiscovery.co.uk/a-west-country-christmas

For more information concerning Landmark Trust properties and holidays at Coombe, click the links below:

https://www.landmarktrust.org.uk/search-and-book/properties/mill-house-2-13563/#History